Ottoman Turkish

| Ottoman Turkish | |

|---|---|

| لسان عثمانی Lisân-ı Osmânî | |

| |

| Region | Ottoman Empire |

| Ethnicity | Ottoman Turks |

| Era | c. 15th century; developed into modern Turkish in 1928[1] |

Turkic

| |

Early form | |

| Ottoman Turkish alphabet | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | ota |

| ISO 639-3 | ota |

ota | |

| Glottolog | otto1234 |

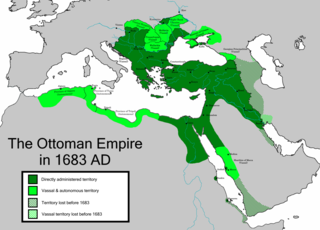

The Ottoman Empire was at its peak, Ottoman Turkish culture including the language also developed in the conquered areas | |

Ottoman Turkish (Ottoman Turkish: لِسانِ عُثمانی, romanized: Lisân-ı Osmânî, Turkish pronunciation: [liˈsaːnɯ osˈmaːniː]; Turkish: Osmanlı Türkçesi) was the standardized register of the Turkish language in the Ottoman Empire (14th to 20th centuries CE). It borrowed extensively, in all aspects, from Arabic and Persian. It was written in the Ottoman Turkish alphabet. Ottoman Turkish was largely unintelligible to the less-educated lower-class and to rural Turks, who continued to use kaba Türkçe ("raw/vulgar Turkish"; compare Vulgar Latin and Demotic Greek), which used far fewer foreign loanwords and is the basis of the modern standard.[3] The Tanzimât era (1839–1876) saw the application of the term "Ottoman" when referring to the language[4] (لسان عثمانی lisân-ı Osmânî or عثمانلیجه Osmanlıca); Modern Turkish uses the same terms when referring to the language of that era (Osmanlıca and Osmanlı Türkçesi). More generically, the Turkish language was called تركچه Türkçe or تركی Türkî "Turkish".

History

[edit]Historically, Ottoman Turkish was transformed in three eras:

- Eski Osmanlı Türkçesi اسکی عثمانلی تورکچهسی (Old Ottoman Turkish): the version of Ottoman Turkish used until the 16th century. It was almost identical with the Turkish used by Seljuk empire and Anatolian beyliks and was often regarded as part of Eski Anadolu Türkçesi اسکی آناطولی تورکچهسی (Old Anatolian Turkish).

- Orta Osmanlı Türkçesi اورتا عثمانلی تورکچهسی (Middle Ottoman Turkish) or Klasik Osmanlıca (Classical Ottoman Turkish): the language of poetry and administration from the 16th century until Tanzimat.

- Yeni Osmanlı Türkçesi یڭی عثمانلی تورکچهسی (New Ottoman Turkish): the version shaped from the 1850s to the 20th century under the influence of journalism and Western-oriented literature.

Language reform

[edit]In 1928, following the fall of the Ottoman Empire after World War I and the establishment of the Republic of Turkey, widespread language reforms (a part in the greater framework of Atatürk's Reforms) instituted by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk saw the replacement of many Persian and Arabic origin loanwords in the language with their Turkish equivalents. One of the main supporters of the reform was the Turkish nationalist Ziya Gökalp.[5] It also saw the replacement of the Perso-Arabic script with the extended Latin alphabet. The changes were meant to encourage the growth of a new variety of written Turkish that more closely reflected the spoken vernacular and to foster a new variety of spoken Turkish that reinforced Turkey's new national identity as being a post-Ottoman state.[citation needed]

See the list of replaced loanwords in Turkish for more examples of Ottoman Turkish words and their modern Turkish counterparts. Two examples of Arabic and two of Persian loanwords are found below.

| English | Ottoman | Modern Turkish |

|---|---|---|

| obligatory | واجب vâcib | zorunlu |

| hardship | مشكل müşkül | güçlük |

| city | شهر şehir | kent (also şehir) |

| province | ولایت vilâyet | il |

| war | حرب harb | savaş |

Legacy

[edit]Historically speaking, Ottoman Turkish is the predecessor of modern Turkish. However, the standard Turkish of today is essentially Türkiye Türkçesi (Turkish of Turkey) as written in the Latin alphabet and with an abundance of neologisms added, which means there are now far fewer loan words from other languages, and Ottoman Turkish was not instantly transformed into the Turkish of today. At first, it was only the script that was changed, and while some households continued to use the Arabic system in private, most of the Turkish population was illiterate at the time, making the switch to the Latin alphabet much easier. Then, loan words were taken out, and new words fitting the growing amount of technology were introduced. Until the 1960s, Ottoman Turkish was at least partially intelligible with the Turkish of that day. One major difference between Ottoman Turkish and modern Turkish is the latter's abandonment of compound word formation according to Arabic and Persian grammar rules. The usage of such phrases still exists in modern Turkish but only to a very limited extent and usually in specialist contexts; for example, the Persian genitive construction takdîr-i ilâhî (which reads literally as "the preordaining of the divine" and translates as "divine dispensation" or "destiny") is used, as opposed to the normative modern Turkish construction, ilâhî takdîr (literally, "divine preordaining").

In 2014, Turkey's Education Council decided that Ottoman Turkish should be taught in Islamic high schools and as an elective in other schools, a decision backed by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who said the language should be taught in schools so younger generations do not lose touch with their cultural heritage.[6]

Writing system

[edit]

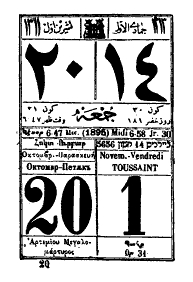

Most Ottoman Turkish was written in the Ottoman Turkish alphabet (Ottoman Turkish: الفبا, romanized: elifbâ), a variant of the Perso-Arabic script. The Armenian, Greek and Rashi script of Hebrew were sometimes used by Armenians, Greeks and Jews. (See Karamanli Turkish, a dialect of Ottoman written in the Greek script; Armeno-Turkish alphabet)

Grammar

[edit]

The actual grammar of Ottoman Turkish is not different from the grammar of modern Turkish.The focus of this section is on the Ottoman orthography; the conventions surrounding how the orthography interacted and dealt with grammatical morphemes related to conjugations, cases, pronouns, etc.

Cases

[edit]- Nominative and Indefinite accusative/objective: -∅, no suffix. گول göl 'the lake' 'a lake', چوربا çorba 'soup', گیجه gece 'night'; طاوشان گترمش ṭavşan getirmiş 'he/she brought a rabbit'.

- Genitive: suffix ڭ/نڭ –(n)ıñ, –(n)iñ, –(n)uñ, –(n)üñ. پاشانڭ paşanıñ 'of the pasha'; كتابڭ kitabıñ 'of the book'.

- Definite accusative: suffix ی –ı, -i: طاوشانی گترمش ṭavşanı getürmiş 'he/she brought the rabbit'. The variant suffix –u, –ü does not occur in Ottoman Turkish orthography (unlike in Modern Turkish), although it's pronounced with the vowel harmony. Thus, گولی göli 'the lake' vs. Modern Turkish gölü.[7]

- Dative: suffix ه –e: اوه eve 'to the house'.

- Locative: suffix ده –de, –da: مكتبده mektebde 'at school', قفسده ḳafeṣde 'in (the/a) cage', باشده başda 'at a/the start', شهرده şehirde 'in town'. The variant suffix used in Modern Turkish (–te, –ta) does not occur.

- Ablative: suffix دن –den, -dan: ادمدن adamdan 'from the man'.

- Instrumental: suffix or postposition ایله ile. Generally not counted as a grammatical case in modern grammars.

Table below lists nouns with a variety of phonological features that come into play when taking case suffixes. The table includes a typical singular and plural noun, containing back and front vowels, words that end with the letter ه ـه ([a] or [e]), both back and front vowels, word that ends in a ت ([t]) sound, and word that ends in either ق or ك ([k]). These words are to serve as references, to observe orthographic conventions:

- Which vowels are written using the 4 letters: ʾalif ا, wāw و, hāʾ ه ـه, and yāʾ ي; and which are not;

- Where words or morphemes are connected to each other, and where they are separated with the use of Zero-width non-joiner.

- where a final letter is softened when followed by a vowel sound, and when not; both in Ottoman orthography and in modern Latin orthography.

- Where harmony of vowel roundness exists in spoken pronounciation, and in modern Latin orthography, but not in Ottoman orthography.

- Where the letter ڭ is used and when the letter ن.

| Case | Morpheme | اُوق | اُوقلَر | اَو | اَولَر | قورت | چارطاق | ایپك | پاره | پیده | كوپری | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ok 'arrow' |

oklar 'arrows' |

ev 'house' |

evler 'houses' |

kurt 'wolf' |

çartak 'gazebo' |

ipek 'silk' |

para 'money' |

pide 'pita' |

köprü 'bridge' | ||||||||||||

| Nom | — | اوق | ok | اوقلر | oklar | او | ev | اولر | evler | قورت | kurt | چارطاق | çartak | ایپك | ipek | پاره | para | پیده | pide | كوپری | köprü |

| Acc | - ـی | اوقی | oku | اوقلری | okları | اوی | evi | اولری | evleri | قوردی | kurdu | چارطاغی | çartağı | ایپگی | ipeği | پارهیی | parayı | پیدهیی | pideyi | كوپریی | köprüyü |

| -ı -i -u -ü | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Dat | - ـه / - ه | اوقه | oka | اوقلره | oklara | اوه | eve | اولره | evlere | قورده | kurda | چارطاغه | çartağa | ایپگه | ipeğe | پارهیه | paraya | پیدهیه | pideye | كوپریه | köprüye |

| -a -e | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Loc | - ده | اوقده | okta | اوقلرده | oklarda | اوده | evde | اولرده | evlerde | قورتده | kurt'ta | چارطاقده | çartakta | ایپكده | ipekde | پارهده | parada | پیدهده | pidede | كوپریده | köprüde |

| -da -de -ta -te | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Alb | - دن | اوقدن | oktan | اوقلردن | oklardan | اودن | evden | اولردن | evlerden | قورتدن | kurttan | چارطاقدن | çartaktan | ایپكدن | ipekden | پارهدن | paradan | پیدهدن | pideden | كوپریدن | köprüden |

| -dan -den -tan -ten | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Gen | - ـڭ | اوقڭ | okun | اوقلرڭ | okların | اوڭ | evin | اولرڭ | evlerin | قوردڭ | kurdun | چارطاغڭ | çartağın | ایپگڭ | ipeğin | پارهنڭ | paranın | پیدهنڭ | pidenin | كوپرینڭ | köprünün |

| -ın -in -un -ün | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Inst | - ـله | اوقله | okla | اوقلرله | oklarla | اوله | evle | اولرله | evlerle | قورتله | kurtla | چارطاقله | çartakla | ایپكله | ipekle | پارهیله | parala | پیدهیله | pidele | كوپریله | köprülü |

| -la -le -lu -lü | |||||||||||||||||||||

Possessives

[edit]Table below shows the suffixes for creating possessed nouns. Each of these possessed nouns, in turn, take case suffixes as shown above.

| Person | Morpheme | اُوق | اُوقلَر | اَو | اَولَر | قورت | چارطاق | ایپك | پاره | پیده | كوپری | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ok 'arrow' |

oklar 'arrows' |

ev 'house' |

evler 'houses' |

kurt 'wolf' |

çartak 'gazebo' |

ipek 'silk' |

para 'money' |

pide 'pita' |

köprü 'bridge' | ||||||||||||

| — | — | اوق | ok | اوقلر | oklar | او | ev | اولر | evler | قورت | kurt | چارطاق | çartak | ایپك | ipek | پاره | para | پیده | pide | كوپری | köprü |

| 1st Person Sg. | - ـم | اوقم | okum | اوقلرم | oklarım | اویم | evim | اولرم | evlerim | قوردم | kurdum | چارطاغم | çartağım | ایپگم | ipeğim | پارهم | param | پیدهم | pidem | كوپریم | köprüm |

| -m -ım -im -um -üm | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 2nd Person Sg. | - ـڭ | اوقڭ | okun | اوقلرڭ | okların | اویڭ | evin | اولرڭ | evlerin | قوردڭ | kurdun | چارطاغڭ | çartağın | ایپگڭ | ipeğin | پارهڭ | paran | پیدهڭ | piden | كوپریڭ | köprün |

| -n -ın -in -un -ün | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 3rd Person Sg. | - ـی - ـسی | اوقی | oku | اوقلری | okları | اوی | evi | اولری | evleri | قوردی | kurdu | چارطاغی | çartağı | ایپگی | ipeği | پارهسی | parası | پیدهسی | pidesi | كوپریسی | köprüsü |

| -(s)ı -(s)i -(s)u -(s)ü | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1st Person Pl. | - ـمز | اوقمز | okumuz | اوقلرمز | oklarımız | اومز | evimiz | اولرمز | evlerimiz | قوردمز | kurdumuz | چارطاغمز | çartağımız | ایپگمز | ipeğimiz | پارهمز | paramız | پیدهمز | pidemiz | كوپریمز | köprümüz |

| -(ı)mız -(i)miz -(u)muz -(ü)müz | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 2nd Person Pl. | - ـڭز | اوقڭز | okunuz | اوقلرڭز | oklarınız | اوڭز | eviniz | اولرڭز | evleriniz | قوردڭز | kurdunuz | چارطاغڭز | çartağınız | ایپگڭز | ipeğiniz | پارهڭز | paranız | پیدهڭز | pideniz | كوپریڭز | köprünüz |

| -(ı)nız -(i)niz -(u)nuz -(ü)nüz | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 3rd Person Pl. | - ـلری | اوقلری | okları | اوقلرلری | okları | اولری | evleri | اولرلری | evleri | قورتلری | kurtları | چارطاقلری | çartakleri | ایپكلری | ipekleri | پارهلری | paraları | پیدهلری | pideleri | كوپریلری | köprüleri |

| -ları -leri | |||||||||||||||||||||

For third person (singular and plural) possessed nouns, that end in a vowel, when it comes to taking case suffixes, a letter - ـنـ [n] comes after the possessive suffix. For singular endings, the final vowel ی is removed in all instances. For plural endings, if the letter succeeding the additional - ـنـ [n] is a vowel, the final vowel ی is kept; otherwise it is removed (note the respective examples for kitaplarını versus kitaplarından). Examples below :

| Nom | Acc | Dat | Loc | Abl | Gen | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| his/her book | کتابی | کتابنی | کتابنه | کتابنده | کتابندن | کتابنڭ |

| kitabı | kitabını | kitabına | kitabında | kitabından | kitabının | |

| his/her books | کتابلری | کتابلرینی | کتابلرینه | کتابلرنده | کتابلرندن | کتابلرینڭ |

| kitapları | kitaplarını | kitaplarına | kitaplarında | kitaplarından | kitaplarının | |

| his/her maternal aunt | تیزهسی | تیزهسنی | تیزهسنه | تیزهسنده | تیزهسندن | تیزهسنڭ |

| teyzesi | teyzesini | teyzesine | teyzesinde | teyzesinden | teyzesinin | |

| his/her maternal aunts | تیزهلری | تیزهلرینی | تیزهلرینه | تیزهلرنده | تیزهلرندن | تیزهلرینڭ |

| teyzeleri | teyzelerini | teyzelerine | teyzelerinde | teyzelerinden | teyzelerinin |

Verbs

[edit]Below table shows the positive conjugation for two sample verbs آچمق açmak (to open) and سولمك sevilmek (to be loved). The first verb is the active verb, and the other has been modified to form a passive verb. The first contains back vowels, the second front vowels; both containing non-rounded vowels (which also impacts pronounciation and modern Latin orthograhpy).[9]

| آچمق açmak 'To open' |

سولمك sevilmek 'To be loved' | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Indicative

|

Present Imperfect am/is/are opening am/is/are being loved |

آچیورم | açıyorum | آچیورز | açıyoruz | سولیورم | seviliyorum | سولیورز | seviliyoruz |

| آچیورسن | açıyorsun | آچیورسڭز | açıyorsunuz | سولیورسن | seviliyorsun | سولیورسڭز | seviliyorsunuz | ||

| آچیور | açıyor | آچیورلر | açıyorlar | سولیور | seviliyor | سولیورلر | seviliyorlar | ||

| Past Imperfect was/were opening was/were being loved |

آچیوردم | açıyordum | آچیوردق | açıyorduk | سولیوردم | seviliyordum | سولیوردك | seviliyorduk | |

| آچیوردڭ | açıyordun | آچیوردڭز | açıyordunuz | سولیوردڭ | seviliyordun | سولیوردڭز | seviliyordunuz | ||

| آچیوردی | açıyordu | آچیوردیلر | açıyordular | سولیوردی | seviliyordu | سولیوردیلر | seviliyordular | ||

| Present Aorist shall habitually open shall habitually be loved |

آچارم | açarım | آچارز | açarız | سولورم | sevilirim | سولورز | seviliriz | |

| آچارسن | açarsın | آچارسڭز | açarsınız | سولورسن | sevilirsin | سولورسڭز | sevilirsiniz | ||

| آچار | açar | آچارلر | açarlar | سولور | sevilir | سولورلر | sevilirler | ||

| Past Perfect opened was loved |

آچدم | açtım | آچدق | açtık | سولدم | sevildim | سولدك | sevildik | |

| آچدڭ | açtın | آچدڭز | açtınız | سولدڭ | sevildin | سولدڭز | sevildiniz | ||

| آچدی | açtı | آچدیلر | açtılar | سولدی | sevildi | سولدیلر | sevildiler | ||

| Future will open will be loved |

آچهجغم | açacağım | آچهجغز | açacağız | سولهجگم | sevileceğim | سولهجگز | sevileceğiz | |

| آچهجقسن | açacaksın | آچهجقسڭز | açacaksınız | سولهجكسن | sevileceksin | سولهجكسڭز | sevileceksiniz | ||

| آچهجق | açacak | آچهجقلر | açacaklar | سولهجك | sevilecek | سولهجكلر | sevilecekler | ||

Inferential

|

Perfect have/has opened, I believe was/were loved, I believe |

آچمشم | açmışım | آچمشز | açmışız | سولمشم | sevilmişim | سولمشز | sevilmişiz |

| آچمشسن | açmışsın | آچمشسڭز | açmışsınız | سولمشسن | sevilmişsin | سولمشسڭز | sevilmişsiniz | ||

| آچمش آچمشدر |

açmış açmışdır |

آچمشلر | açmışlar | سولمش سولمشدر |

sevilmiş sevilmişdir |

سولمشلر | sevilmişler | ||

Necessitative

|

Aorist must open must be loved |

آچملویم | açmalıyım | آچملویز | açmalıyız | سولملویم | sevilmeliyim | سولملویز | sevilmeliyiz |

| آچملوسن | açmalısın | آچملوسڭز | açmalısınız | سولملوسن | sevilmelisin | سولملوسڭز | sevilmelisiniz | ||

| آچملو | açmalı | آچملولر | açmalılar | سولملو | sevilmeli | سولملولر | sevilmeliler | ||

| Past must've open must've bee loved |

آچملویدم | açmalıydım | آچملویدق | açmalıydık | سولملویدم | sevilmeliydim | سولملویدق | sevilmeliydik | |

| آچملویدڭ | açmalıydın | آچملویدڭز | açmalıydınız | سولملویدڭ | sevilmeliydin | سولملویدڭز | sevilmeliydiniz | ||

| آچملویدی | açmalıydı | آچملویدیلر | açmalıydılar | سولملویدی | sevilmeliydi | سولملویدیلر | sevilmeliydiler | ||

Optative

|

Present that may open that may be loved |

آچهیم | açayım | آچهیز آچهلم |

açayız açalım |

سولهیم | sevileyim | سولهیز سولهلم |

sevileyiz sevilelim |

| آچهسن | açasın | آچهسڭز | açasınız | سولهسن | sevilesin | سولهسڭز | sevilesiniz | ||

| آچه | aça | آچهلر | açalar | سوله | sevile | سولهلر | sevileler | ||

Conditional

|

Aorist if open if be loved |

آچسم | açsam | آچسق | açsak | سولسم | sevilsem | سولسك | sevilsek |

| آچسڭ | açsan | آچسڭز | açsanız | سولسڭ | sevilsen | سولسڭز | sevilseniz | ||

| آچسه | açsa | آچسهلر | açsalar | سولسه | sevilse | سولسهلر | sevilseler | ||

| Past if opened if were loved |

آچسیدم | açsaydım | آچسیدق | açsaydık | سولسیدم | sevilseydim | سولسیدك | sevilseydik | |

| آچسیدڭ | açsaydın | آچسیدڭز | açsaydınız | سولسدیڭ | sevilseydin | سولسیدڭز | sevilseydiniz | ||

| آچسیدی | açsaydı | آچسیدیلر | açsaydılar | سولسیدی | sevilseydi | سولسیدیلر | sevilseydiler | ||

| Imperative | - | - | آچالم | açalım | - | - | سولهلم | sevilelim | |

| آچ آچڭ |

aç açın |

آچڭز | açınız | سول سولڭ |

sevil sevilin |

سولڭز | seviliniz | ||

| آچسون | açsın | آچسونلر | açsınlar | سولسون | sevilsin | سولسونلر | sevilsinler | ||

Negation and complex verbs

[edit]Below table shows the conjugation of a negative verb, and a positive complex verb expressing ability. In Turkish, complex verbs can be constructed by adding a variety of suffixes to the base root of a verb. The two verbs are یازممق yazmamaq (not to write) and سوهبلمك sevebilmek (to be able to love).[9]

| یازممق yazmamaq 'Not to write' |

سوهبلمك sevebilmek 'To be able to love' | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Indicative

|

Present Imperfect am/is/are not writing can love |

یازمیورم | yazmayorum | یازمیورز | yazmayoruz | سوهبیلیورم | sevebiliyorum | سوهبیلیورز | sevebiliyoruz |

| یازمیورسن | yazmayorsun | یازمیورسڭز | yazmayorsunuz | سوهبیلیورسن | sevebiliyorsun | سوهبیلیورسڭز | sevebiliyorsunuz | ||

| یازمیور | yazmayor | یازمیورلر | yazmayorlar | سوهبیلیور | sevebiliyor | سوهبیلیورلر | sevebiliyorlar | ||

| Past Imperfect was/were not writing was/were able to love |

یازمیوردم | yazmıyordum | یازمیوردق | yazmıyorduk | سوهبیلیوردم | sevebiliyordum | سوهبیلیوردك | sevebiliyorduk | |

| یازمیوردڭ | yazmıyordun | یازمیوردڭز | yazmıyordunuz | سوهبیلیوردڭ | sevebiliyordun | سوهبیلیوردڭز | sevebiliyordunuz | ||

| یازمیوردی | yazmıyordu | یازمیوردیلر | yazmıyordular | سوهبیلیوردی | sevebiliyordu | سوهبیلیوردیلر | sevebiliyordular | ||

| Present Aorist do not write shall be able to love |

یازمم | yazmam | یازمیز | yazmayız | سوهبلورم | sevebilirim | سوهبلورز | sevebiliriz | |

| یازمازسن | yazmazsın | یازمازسڭز | yazmazsınız | سوهبلورسن | sevebilirsin | سوهبلورسڭز | sevebilirsiniz | ||

| یازماز | yazmaz | یازمازلر | yazmazlar | سوهبلور | sevebilir | سوهبلورلر | sevebilirler | ||

| Past Perfect used not to write could love |

یازمادم | yazmadım | یازمادق | yazmadık | سوهبلدم | sevebildim | سوهبلدك | sevebildik | |

| یازمادڭ | yazmadın | یازمادڭز | yazmadınız | سوهبلدڭ | sevebildin | سوهبلدڭز | sevebildiniz | ||

| یازمادی | yazmadı | یازمادیلر | yazmadılar | سوهبلدی | sevebildi | سوهبلدیلر | sevebildiler | ||

| Future shall not write will be able to love |

یازمیهجغم | yazmayacağım | یازمیهجغز | yazmayacağız | سوهبلهجگم | sevibileceğim | سوهبلهجگز | sevibileceğiz | |

| یازمیهجقسن | yazmayacaksın | یازمیهجقسڭز | yazmayacaksınız | سوهبلهجكسن | sevibileceksin | سوهبلهجكسڭز | sevibileceksiniz | ||

| یازمیهجق | yazmayacak | یازمیهجقلر | yazmayacaklar | سوهبلهجك | sevibilecek | سوهبلهجكلر | sevibilecekler | ||

Necessitative

|

Aorist must open must be loved |

یازمهملییم | yazmamalıyım | یازمهملییز | yazmamalıyız | سوهبلملییم | sevibilmeliyim | سوهبلملییز | sevibilmeliyiz |

| یازمهملیسن | yazmamalısın | یازمهملیسڭز | yazmamalısınız | سوهبلملیسن | sevibilmelisin | سوهبلملیسڭز | sevibilmelisiniz | ||

| یازمهملی | yazmamalı | یازمهملیلر | yazmamalılar | سوهبلملی | sevibilmeli | سوهبلملیلر | sevibilmeliler | ||

Optative

|

Present that may not open that may not be able to love |

یازمیهیم | yazmayayım | یازمیهیز یازمیهلم |

yazmayayız yazmayalım |

سوهبلهیم | sevibileyim | سوهبلهیز سوهبلهلم |

sevibileyiz sevibilelim |

| یازمیهسن | yazmayasın | یازمیهسڭز | yazmayasınız | سوهبلهسن | sevibilesin | سوهبلهسڭز | sevibilesiniz | ||

| یازمیه | yazmaya | یازمیهلر | yazmayalar | سوهبله | sevibile | سوهبلهلر | sevibileler | ||

| Imperative | - | - | یازمیهلم | yazmayalım | - | - | سوبلهلم | sevibilelim | |

| یازمه یازمیڭ |

yazma yazmayın |

یازمیڭز | yazmayınız | سوبل سوبلڭ |

sevibil sevibilin |

سوبلڭز | sevibiliniz | ||

| یازمسون | yazmasın | یازمسونلر | yazmasınlar | سوبلسون | sevibilsin | سوبلسونلر | sevibilsinler | ||

Compound verbs

[edit]Another common category of verbs in Turkish (more common in Ottoman Turkish than in modern Turkish), is compound verbs. This consists of adding a Persian or Arabic active or passive participle to a neuter verb, to do (ایتمك etmek) or to become (اولمق olmaq). For example, note the following two verbs:

- راضی اولمق razı olmaq (to consent)

- قتل ایتمك katletmek (to slaughter).

Below table shows some sample conjugations of these two verbs. The conjugation of the verb "etmek" isn't straightforward, because the root of the verb ends in a [t]. This sound transforms into a [d] when followed by a vowel sound. This is reflected in conventions of Ottoman orthography as well.

Structure

[edit]

Ottoman Turkish was highly influenced by Arabic and Persian. Arabic and Persian words in the language accounted for up to 88% of its vocabulary.[10] As in most other Turkic and foreign languages of Islamic communities, the Arabic borrowings were borrowed through Persian, not through direct exposure of Ottoman Turkish to Arabic, a fact that is evidenced by the typically Persian phonological mutation of the words of Arabic origin.[11][12][13]

The conservation of archaic phonological features of the Arabic borrowings furthermore suggests that Arabic-incorporated Persian was absorbed into pre-Ottoman Turkic at an early stage, when the speakers were still located to the north-east of Persia, prior to the westward migration of the Islamic Turkic tribes. An additional argument for this is that Ottoman Turkish shares the Persian character of its Arabic borrowings with other Turkic languages that had even less interaction with Arabic, such as Tatar, Bashkir, and Uyghur. From the early ages of the Ottoman Empire, borrowings from Arabic and Persian were so abundant that original Turkish words were hard to find.[14] In Ottoman, one may find whole passages in Arabic and Persian incorporated into the text.[14] It was however not only extensive loaning of words, but along with them much of the grammatical systems of Persian and Arabic.[14]

In a social and pragmatic sense, there were (at least) three variants of Ottoman Turkish:

- Fasih Türkçe فصیح تورکچه (Eloquent Turkish): the language of poetry and administration, Ottoman Turkish in its strict sense;

- Orta Türkçe اورتا تورکچه (Middle Turkish): the language of higher classes and trade;

- Kaba Türkçe قبا تورکچه (Rough Turkish): the language of lower classes.

A person would use each of the varieties above for different purposes, with the fasih variant being the most heavily suffused with Arabic and Persian words and kaba the least. For example, a scribe would use the Arabic asel (عسل) to refer to honey when writing a document but would use the native Turkish word bal when buying it.

Numbers

[edit]1 |

١ |

بر |

bir |

2 |

٢ |

ایكی |

iki |

3 |

٣ |

اوچ |

üç |

4 |

٤ |

درت |

dört |

5 |

٥ |

بش |

beş |

6 |

٦ |

آلتی |

altı |

7 |

٧ |

یدی |

yedi |

8 |

٨ |

سكز |

sekiz |

9 |

٩ |

طقوز |

dokuz |

10 |

١٠ |

اون |

on |

11 |

١١ |

اون بر |

on bir |

12 |

١٢ |

اون ایکی |

on iki |

Transliterations

[edit]The transliteration system of the İslâm Ansiklopedisi has become a de facto standard in Oriental studies for the transliteration of Ottoman Turkish texts.[16] In transcription, the New Redhouse, Karl Steuerwald, and Ferit Devellioğlu dictionaries have become standard.[17] Another transliteration system is the Deutsche Morgenländische Gesellschaft (DMG), which provides a transliteration system for any Turkic language written in Arabic script.[18] There are few differences between the İA and the DMG systems.

| ا | ب | پ | ت | ث | ج | چ | ح | خ | د | ذ | ر | ز | ژ | س | ش | ص | ض | ط | ظ | ع | غ | ف | ق | ك | گ | ڭ | ل | م | ن | و | ه | ی |

| ʾ/ā | b | p | t | s | c | ç | ḥ | ḫ | d | ẕ | r | z | j | s | ş | ṣ | ż | ṭ | ẓ | ʿ | ġ | f | ḳ | k,g,ñ,ğ | g | ñ | l | m | n | v | h | y |

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Turkey – Language Reform: From Ottoman To Turkish". Countrystudies.us. Archived from the original on 9 April 2016. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- ^ "5662". DergiPark.

- ^ Glenny, Misha (2001). The Balkans — Nationalism, War, and the Great Powers, 1804–1999. Penguin. p. 99.

- ^ Kerslake, Celia (1998). "Ottoman Turkish". In Lars Johanson; Éva Á. Csató (eds.). Turkic Languages. New York: Routledge. p. 108. ISBN 0415082005.

- ^ Aytürk, İlker (July 2008). "The First Episode of Language Reform in Republican Turkey: The Language Council from 1926 to 1931". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 18 (3): 277. doi:10.1017/S1356186308008511. hdl:11693/49487. ISSN 1474-0591. S2CID 162474551.

- ^ Pamuk, Humeyra (December 9, 2014). "Erdogan's Ottoman language drive faces backlash in Turkey". Reuters. Istanbul. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

- ^ Redhouse, William James. A Simplified Grammar of the Ottoman-Turkish Language. p. 52.

- ^ a b Sir James William Redhouse (1884). A simplified grammar of the Ottoman-Turkish language. Trübner.

- ^ a b Charles Wells (1880). A practical grammar of the Turkish language (as spoken and written). B. Quaritch. Online copies from Google Books: [1] (PDF can be accessed at: archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.31137)

- ^ Bertold Spuler. Persian Historiography & Geography Pustaka Nasional Pte Ltd ISBN 9971774887 p 69

- ^ Percy Ellen Algernon Frederick William Smythe Strangford, Percy Clinton Sydney Smythe Strangford, Emily Anne Beaufort Smythe Strangford, "Original Letters and Papers of the late Viscount Strangford upon Philological and Kindred Subjects", Published by Trübner, 1878. pg 46: "The Arabic words in Turkish have all decidedly come through a Persian channel. I can hardly think of an exception, except in quite late days, when Arabic words have been used in Turkish in a different sense from that borne by them in Persian."

- ^ M. Sukru Hanioglu, "A Brief History of the Late Ottoman Empire", Published by Princeton University Press, 2008. p. 34: "It employed a predominant Turkish syntax, but was heavily influenced by Persian and (initially through Persian) Arabic.

- ^ Pierre A. MacKay, "The Fountain at Hadji Mustapha", Hesperia, Vol. 36, No. 2 (Apr. – Jun., 1967), pp. 193–195: "The immense Arabic contribution to the lexicon of Ottoman Turkish came rather through Persian than directly, and the sound of Arabic words in Persian syntax would be far more familiar to a Turkish ear than correct Arabic".

- ^ a b c Korkut Bugday. An Introduction to Literary Ottoman Routledge, 5 dec. 2014 ISBN 978-1134006557 p XV.

- ^ Hagopian, V. H. (1907). Ottoman-Turkish conversation-grammar; a practical method of learning the Ottoman-Turkish language. Heidelberg: J. Groos. p. 89. Retrieved 5 May 2018 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Korkut Buğday Osmanisch, p. 2

- ^ Korkut Buğday Osmanisch, p. 13

- ^ Transkriptionskommission der DMG Die Transliteration der arabischen Schrift in ihrer Anwendung auf die Hauptliteratursprachen der islamischen Welt, p. 9 Archived 2012-07-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Korkut Buğday Osmanisch, p. 2f.

Further reading

[edit]- English

- V. H. Hagopian (1907). Ottoman-Turkish conversation-grammar: a practical method of learning the Ottoman-Turkish language, Volume 1. D. Nutt. Online copies: [2], [3], [4]

- Charles Wells (1880). A practical grammar of the Turkish language (as spoken and written). B. Quaritch. Online copies from Google Books: [5], [6], [7]

- V. H. Hagopian (1908). Key to the Ottoman-Turkish conversation-grammar. Nutt.

- Sir James William Redhouse (1884). A simplified grammar of the Ottoman-Turkish language. Trübner.

- Frank Lawrence Hopkins (1877). Elementary grammar of the Turkish language: with a few easy exercises. Trübner.

- Sir James William Redhouse (1856). An English and Turkish dictionary: in two parts, English and Turkish, and Turkish and English. B. Quarich.

- Sir James William Redhouse (1877). A lexicon, English and Turkish: shewing in Turkish, the literal, incidental, figurative, colloquial, and technical significations of the English terms, indicating their pronunciation in a new and systematic manner; and preceded by a sketch of English etymology, to facilitate to Turkish students ... (2nd ed.). Printed for the mission by A.H. Boyajian.

- Charles Boyd, Charles Boyd (Major.) (1842). The Turkish interpreter: or, A new grammar of the Turkish language. Printed for the author.

- Thomas Vaughan (1709). A Grammar of The Turkish Language. Robinson.

- William Burckhardt Barker (1854). A practical grammar of the Turkish language: With dialogues and vocabulary. B. Quaritch.

- William Burckhardt Barker, Nasr-al-Din (khwajah.) (1854). A reading book of the Turkish language: with a grammar and vocabulary ; containing a selection of original tales, literally translated, and accompanied by grammatical references : the pronunciation of each word given as now used in Constantinople. J. Madden.

- James William Redhouse (sir.) (1855). The Turkish campaigner's vade-mecum of Ottoman colloquial language.

- Lewis, Geoffrey. The Jarring Lecture 2002. "The Turkish Language Reform: A Catastrophic Success".

- Other languages

- Mehmet Hakkı Suçin. Qawâ'id al-Lugha al-Turkiyya li Ghair al-Natiqeen Biha (Turkish Grammar for Arabs; adapted from Mehmet Hengirmen's Yabancılara Türkçe Dilbilgisi), Engin Yayınevi, 2003).

- Mehmet Hakkı Suçin. Atatürk'ün Okuduğu Kitaplar: Endülüs Tarihi (Books That Atatürk Read: History of Andalucia; purification from the Ottoman Turkish, published by Anıtkabir Vakfı, 2001).

- Kerslake, Celia (1998). "La construction d'une langue nationale sortie d'un vernaculaire impérial enflé: la transformation stylistique et conceptuelle du turc ottoman". In Chaker, Salem (ed.). Langues et Pouvoir de l'Afrique du Nord à l'Extrême-Orient. Aix-en-Provence: Edisud. pp. 129–138.

- Korkut M. Buğday (1999). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag (ed.). Osmanisch: Einführung in die Grundlagen der Literatursprache.

External links

[edit]- Latin to Ottoman Turkish transliteration

- Ottoman Text Archive Project

- Ottoman Turkish Language: Resources – University of Michigan

- Ottoman Turkish Language Texts

- Ottoman-Turkish-English Open Dictionary

- Ottoman<->Turkish Dictionary – University of Pamukkale You can use ? character instead of an unknown letter. It provides results from Arabic and Persian dictionaries, too.

- Ottoman<->Turkish Dictionary – ihya.org

- Kubbealtı Lugatı